Towards a View of Hermetic Ethics

Some thoughts on Eusebeia in the Corpus Hermeticum, the Korē Kosmou's Royal Pneumatology & the Good in Hermetism

As part of my contemplations recently, I’ve been thinking about how exactly we define theurgy, both in theory, as a systematic schema and justification of praxis and a practical ritual technique in itself. Crystal Addey’s1 work has been immensely helpful in this regard as a starting point. In her 2014 monograph on Dreams & Astrology in Iamblichus, she defined theurgy as:

“A lifelong endeavour incorporating a set of ritual practices alongside the development of ethical and intellectual capacities, which aimed to use symbols to reawaken the soul’s pre-ontological, causal connection with the gods, operating primarily through divine love and, subordinately, through cosmic sympathy. The goal of theurgy was the cumulative contact, assimilation and, ultimately, union with the divine and thereby the divinization of the theurgist; in other words, the ascent of the soul to the divine, intelligible realm and the manifestation of the divine in embodied life. The ascent to the divine is conceptualized as an ascent of consciousness. Iamblichus maintains that the highest purpose of theurgy is ascent to the One, which was thought to be beyond Being itself; yet this occurs only at a very late stage and to a few individuals”

Her definition is essentially tripartite; theurgy consists of three key areas or pillars -both in theory and practice, 1) Ritual Practices, 2) Ethical (and by proxy, Moral) Education and 3) the cultivation of Intellectual Capacities, most usually through philosophical study2, all with the primary goal of gradual assimilation to (and imitation of) the divine during life, culminating with henosis, otherwise considered the standard teleology of Platonism as worked out by the 1st Century Neopythagorean, Eudorus of Alexandria.

These categories map fairly well onto Valantasis’ dimensions of the role(s) of spiritual guides in the 3rd century in his study on Semiotics3. He notes, in lieu of Ilsetraut Hadot’s work on spiritual exercises in the Late Antique Mediterranean4:

Often the origins of spiritual formation and guidance are ascribed to paideia, from Graeco-Roman educational practices:

[As the beginnings of spiritual guidance in Graeco-Roman antiquity coincided with the beginnings of general education, so too the function of the spiritual guide coincides with that of the educator, insofar as we understand education (paideia) to include the whole of the endeavour to make a person fit for life and, consequently, the formation of a person’s moral attitudes as well]…

Within those relationships (between Master & Student) the guides trained the disciple in a way of perceiving and relating to the mental and emotional self, the religious community, and the wider world. The substance of training revolved around the transmission of traditional material regarding the Interior Life.

I’m fairly content with this definition, although I might add alongside the mental and emotional self, the guide imparted knowledge of the subtle (usually planetary) body -at least in Platonism derived currents, as a framework for working with and facilitating catharsis.

I’ve written elsewhere5 about the caution of considering Addey’s categories as robust or separate dimensions, though. As a holistic, ritualised philosophy, a theurgic ritual and exercise can incorporate all three of these categories at once, and most usually does. So, like Greg Shaw’s distinction of the different kinds of suthenmata (material, intermediary & noetic)6, these are to be considered logical distinctions only. In practice the categories overlap, interweave, and often depend on each other.

The basic theory at play for Iamblichus in theurgy (which differentiates it from magic, for example), is that such practices are engaged to enhance the fitness of a receptacle to receive the gods, most usually -in the case of our own soul, by means of possession of the imagination; which itself has been amplified or purified through engagement with suthenmata (correspondences/tokens). A theurgist does not compel or evoke the gods, not only out piety, but also practicality.

There is simply no reason to. Not only are noetic First Principles above and beyond the realm of generation, and therefore not susceptible to passions or whims of emotion -being wholly and unchangingly good, but Iamblichus is clear that the gods are already omnipresent as subtle divine light all around us. They are embodied in the subtle logoi, reasoned principles that give meaning to and make reality intelligible. I always prefer the analogy that we are “tuning” our perception to a certain wavelength of light by polishing our windows to let the sun in. We can’t control whether the sun shines, but we can filter it like stained glass to allow certain bands in. This is what you’re doing with suthenmata.7

As Greg Shaw notes in his Hellenic Tantra, when asked by his student to come to the temples for the festivals of the gods, Plotinus responded that "they should come to me, not I to them." Plotinus isn't so much being impious/blasphemous here, actually quite the opposite.

He appears to have considered it impious to pester the gods with material things or bother them by continually reaching out and trying to grasp at them for things that are well within our own power to accomplish. Instead, our focus should be on cultivating a state of self in which we are receptive to them. In other words, we shouldn't devote our time to attempting to grasp at the gods, but should focus on increasing our own spiritual fitness so that we provide a state in which we can be grasped by them.

Now, of course, by this logic, a large amount of what are generally titled as Systasis or Ph Ntr in the PGM/PDM would actually qualify as theurgic prayers for Iamblichus, especially the rites to acquire divine favour. It comes down to attitude and approach8. Most of all, one should take on a core understanding that it is the Gods driving the operation.

Greg Shaw put this idea best in a recent talk I attended of his. It’s essentially that experience one has when they’re in meditation, chanting mantras or visualising and come to an awareness that they are not really the one doing anything. You are simply a conduit or vessel for the mantra or experience to chant through you, in the same way people undergoing intense visualisation often report a clear singularity moment in which the Active Imagination takes over and they begin seeing things that they are not consciously creating.

Iamblichus clearly and succinctly explains this process in De Mysteriis9:

Hence it is not even chiefly through our intellection that divine causes are called into actuality; but it is necessary for these and all the best conditions of the soul and our ritual purity to pre-exist as auxiliary causes; but the things which properly arouse the divine will are the actual divine symbols. And so the attention of the gods is awakened by themselves, receiving from no inferior being any principle for themselves of their characteristic activity

Note that first sentence, it’s not our intellectual faculty alone that brings the divine in. Good Intellectual Formation and “the best condition of the soul” alongside ritual purity are necessary perquisites/auxiliary things to do so, but do not complete the operation.

I’ve written a fair bit already on the ritual portion of theurgic work, but the Ethical Education is just as, if not more important, especially for preparing and strengthening the soul for divine reception. Without a thorough grounding in Platonic (or, as I hope to argue, Hermetic) Virtue Ethics, the presence of the divine will undoubtedly overpower the mind and body of the practitioner, or, the individual will be led astray by “barking daimons” (to quote the Oracles10) and false phantasmata (Imaginary Images) derived from the Astral Passions.11 The consequences of such practice is stated fairly well in CH I.23:

Such a person does not cease longing after insatiable appetites, struggling in the darkness without satisfaction. It tortures him and makes the fire grow upon him all the more

More than anything, I am interested right now in Hermetic theurgy, and the ways in which it conforms to & differs from Chaldean or Iamblichean.

So I’m going to take Addey’s three categories of theurgic practice and work them out in Hermetic contexts to see if we can find equivalents or justifications. Hopefully this will present us with some points to compare and contrast with Iamblichus’ view of theurgy and aid in elucidating both systems. To begin, I want to focus on what, I suppose, we can dub as Hermetic Ethics.

From the current philosophical and spiritual Hermetica that we have, what kind of ethical system can be gleaned? What was considered “good behaviour” to a Hermetist? What is the Hermetica’s solution to the problem of evil? What was the theoretical and moral system in which their practice was grounded and worked out, and what was the framework that gave motivation and encouragement to practice Virtue?

I’m not so concerned with specific ethics or behaviours, more the ethical framework that provided the justification. and motivation to practice Virtue.

Eusebeia & Virtues in the Corpus Hermeticum

Plenty is often written about the Corpus Hermeticum, and there is certainly some implied ethical behaviour in there, most centrally the Virtue of Eusebeia, which -as far as I can see, seems to be the Cardinal Hermetic Virtue. Eusebeia in a Hermetic context is essentially reverence for the divine. Although, I will admit, I find Hanegraaff’s argument12 that it is perhaps better understood as a feeling of childlike astonishment at the Form of Beauty & God’s Presence very convincing.

Quoting Anna Van den Kerchove’s fascinating thesis, La Voie d’Hermes13, Hanegraaff points out that the Hermetica never stop praising the astonishing beauty of creation14, while at the same time lamenting the irreverence (asebeia) of those who seem to have lost their sense of wonder and admiration. Notably, Van den Kerchove’s insights are pivotal here:

The translators [of the Corpus]…have used a term that is constructed with a privative or negative particular: dif-fido in Latin, ⲁⲧ-ⲛⲁϩⲧⲉ in Coptic, with perhaps άπιστείν (apistein) in the original Greek version. Each verb is opposed to another one that signifies “being astonished” and “to admire” (miror in Latin and ⲣⲑⲁⲩⲏⲁⲍⲉ in Coptic, constructed after the Greek θαυμάζειν (thaumazein). The astonishment that leads to admiration plays an important role in philosophy; it is the origin of knowledge [Plato, Theaet 155d] and is a motor of contemplation. That being astonished is placed in opposition to lacking faith signifies that astonishment and admiration lead to faith. It appears that the latter has little to do with the classical sense of πιστις (pistis). Linked rather to astonishment and admiration, it would allow the spirit/soul to elevate itself to another reality that is hidden from what appears to the eye.

I am reminded in her discussion of Socratic Eros as the driving force behind the soul’s ascent in dialogues like the Phaedrus, Phaedo & Symposium. Philosophia for Socrates is perhaps even better characterised as Erosophia, a desire for knowledge and perception of the Forms driven by passionate love, not simply friendship (philia). Eros can help the soul remember the Form of Beauty in its purest ideal because we are driven to pursue or court it like a lover. It follows from this that, for Plato, Eros directly contributes to an understanding of truth; something that lies at the very foundation of Platonic Love.

Back with eusebeia though, the Greek root σεβ from which eusebeia comes, denotes a sense of awe at sacred things, and during the Classical Period, the word denoted actions appropriate to the gods. Originally it seems to have meant behaving as tradition dictates in one's social relationships and divine matters. We demonstrate eusebeia to the gods by performing the customary acts of respect; things like festivals, prayers, sacrifices and public devotions.

An interesting parallel is Theoria. The term originally denoted an act of pilgrimage to a temple or sacred site with the intention to view the sacred cult objects of the deity15. Under Plato’s spiritualisation of the term, the “sacred objects” or idols of viewing and contemplation became the Forms themselves. However, the original context still subtly remains. Theoria as a kind of contemplative “journey” to the “cult objects” of the Forms is -in my view, still to be considered part of the “right conduct” paid to sacred things espoused by traditional eusebeia.

In a Platonic context, it simply denotes the “right” conduct paid to gods, and to the Stoics, it meant knowledge of how God should be worshiped. The “act of respect” and “right conduct” for the Hermetic Pēgē then, is simply admiration, love and awe at its creation, which takes on a central and cardinal position in Hermetic Spirituality as the highest Virtue.

It is also interesting to note that Eusebeia was personified in myth as a daimon herself, one who ruled over piety, loyalty, duty and filial respect in opposition to Dyssebeia, the daimon who ruled the opposite16.

Hanegraaff is correct -I think, in asserting that eusebeia is characterised as an attitude of profound respect or awe that can be captured along an ascending scale of intensity by terms in English like “reverence”, “admiration” and “veneration”, which are all modalities of love. We are dealing not with fear of the divine, but with a spontaneous positive response to things that participate in the Form of Beauty.

For the Hermetica, such things are assumed a triadic conception. That is, it is taken for granted that what is Beautiful exists in a trinity of what is Good and True. This transcendent triad of The Good, the Beautiful and the True and their essential unity is assumed essentially as a given in CH VIII.3 and XI. 13. As a nuance though, Hanegraaff poignantly asserts that17:

While this reality is held to be both Good and True, it is experienced as Beauty. For those who were previously confused or blind, their initial response to such experiences is captured most clearly by the verb θαυμαζειν, referring to noetic experiences of astonishment and wonder.

This view makes sense when we understand the semiotics and intended reception of the Hermetica.

If we examine the relationship between Hermes & Tat (or Asclepius), it’s abundantly clear there is an idealistic tone the dialogues. That is, with the Corpus Hermeticum, we’re not necessarily dealing with a Hermetic Paideia as it worked in practice, but the idealised form of its teaching. Both Christian Bull & Wouter Hanegraaff have lent discussions to the portrayal of Hermes as the Model Teacher and Asclepius as the Model Student. We have to therefore be aware of numerous filters and lenses placed over the texts. Not only are we dealing with the Byzantine filter in terms of editorial decisions, but also an idealistic one on the part of the authors.

While Hermetic dialogues are undoubtedly modelled off the Platonic style, we are not dealing with rational interlocution or philosophical arguments here. Hermes as the teacher is presenting Revelatory Knowledge, especially that gleaned through Gnosis -personal, transcendent insight of the Source, and Asclepius willingly submits and reveres such wisdom, oftentimes without question. The occasions in which the student questions the Master are few and far between. The Hermetica therefore have much more in common with Revelatory Discourse than they do with Philosophical18.

This is part of the reason that honestly…philosophically speaking the Hermetica aren’t really that interesting or unique. In a weird way, I actually find myself agreeing with Father Festugière. If read as philosophy, the Hermetica certainly pale in comparison to Plato and fall far short of other contemporary philosophical systems. But they aren’t meant to be philosophical in the Classical sense. They are revelatory dialogues with a soteriological aim that use philosophy (and spiritual exercises) as a medium to communicate their wisdom.

We do nevertheless glimpse an aspect of the model student here. Asclepius reveres Hermes as a divine sage presenting unchanging wisdom. His attitude is characterised as one of reverence, receptivity and acceptance, with gnosis as his highest desire and goal. The times in which he does question Hermes are merely requests for elaborations and expansion. Even in the Nag Hammadi collection, things like the Prayer of Thanksgiving espouse the gratitude for Mind, Understanding & Wisdom and ask -maybe even better characterised as wish, not to “stray from gnosis while in life”.

Virtue & Ignorance in the Asclepius

Another series of key passages to examine come from the Logos Teleios, known under its Latin translation, the Asclepius. Ascl 11 is a fascinating insight into aspects of Virtue:

For him-mankind that is, and for the sum of his parts, the ultimate standard is Eusebeia, from which Goodness follows. Goodness is deemed perfect only when fortified by the virtue of Disdain, which repels desire for every alien thing. Any earthly possessions owned out of bodily desire are all alien to every part of his divine kinship. To name such things “possessions” is correct because they do not come to be with us but come to be possessed by us later on, wherefore we call them by the name “possessions”. Everything of this kind, then, is alien to humanity, even the body, and we should despise both things we yearn for and the source within us of the vice of Yearning. The aim of the argument leads me to think that humanity was bound to be human only to this extent, that by contemplating divinity he should scorn and despise that moral part joined to him by the need to preserve the lower world. Now, in order for humanity in both his parts to have all that he can, note that he was formed with a quaternary of elements in either part: with pairs of hands and feet and other bodily members to serve the lower or earthly world; and with those four faculties of Thought, Consciousness, Memory and Foresight by means of which he knows all things divine and looks up to them. Hence, searching warily, humanity hunts in things for variations, qualities, effects and quantities, and yet, because the heavy and excessive vice of body slows him down, he cannot rightly discern the true causes of their nature

I’d also give attention to the next section in which our goal and purpose as embodied humans is outlined:

Seeing the world is God’s work, one who attentively preserves and enriches its beauty conjoins his own work with God’s will when, lending his body in daily work and care, he arranges the scene formed by God’s divine intention

There’s a few things in here to pull out. Notably, in the first few lines we glimpse some descriptions of Virtues, namely eusebeia -as usual, but also Goodness and Disdain -said to fortify or improve our perception19 of Goodness. On the surface this seems odd, how can disdain be a Virtue, given it -on the surface, implies a dualist anti-matter view that seems antithetical to Hermetic Embodiment? Well, to me the Disdain which “repels every alien thing” -most importantly a sense of desire or yearning for material things, reads more like the sense of Non-Attatchment (nekkhamma) we read about in Buddhism.

We’re talking about a state in which a person overcomes their emotional attachment to or desire for things, people, or worldly concerns by emphasising the temporary nature of the physical body and the true nature of matter. In Zen Buddhism, the Chinese term wú niàn (無念) is often used for it and literally means "no thought." This doesn’t signify a literal absence of thought, but rather a state of being "unstained" bù rán 不染 by one’s thoughts. Detachment then, is being detached from our thoughts; separating ourself from our own thoughts and opinions in detail so we are not harmed mentally and emotionally by them. In this sense it is more or less identical to the Stoic apatheia, i.e equanimity.

It’s no small thing that Yearning is specifically identified as a Vice here too. But notice the role of Humanity here. We are granted embodiment:

To serve the lower or earthly world; and with those four faculties of Thought, Consciousness, Memory and Foresight by means of which he knows all things divine and looks up to them

The ideal Hermetic practitioner should aim to ‘give birth in beauty’ and contribute to the maintenance and beautification of the world to make it better reflect God’s Image, which we are capable of perceiving -or at least, contemplating, through our mental faculties provided the negative constraints of matter and the sub lunary astral forces are overcome. Notably, we are told that:

One who attentively preserves and enriches [the world’s] beauty conjoins his own work with God’s will when, lending his body in daily work and care, he arranges the scene formed by God’s divine intention

So, we cannot be taken out of the world, since we are the ones responsible for bringing the Divine Light of the Gods into it. It’s difficult stuff, we are constantly slowed down in our mission by the “heavy and excessive vice of the body”, which impedes our ability to perceive God’s will. A nuance could be argued here though. The body qua body does not slow us down per se… the Vice of the body does. It is the Harmful Passions of Yearning, Lust, Ignorance and Desire that are the problem, not the body itself, a conclusion Hanegraaff equally espouses.

There’s a natural tendency to assume Christian ethics when we think of morality, especially with notions of sin. But there is no sin in Hermetica, just as there is no hell or, really, Divine Fall.

The Astral Passions, False Images & Non-Dualism

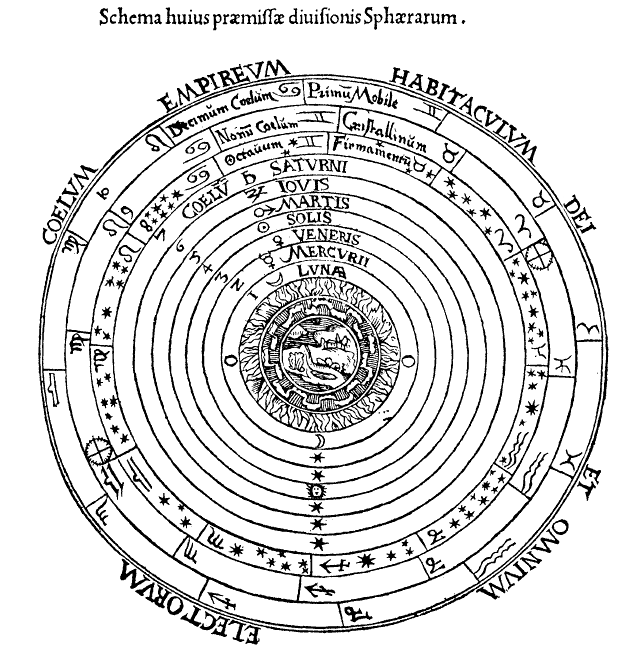

The other seemingly obvious sections in what we can assume comments on Virtues or Vices are the numerous references to Passions throughout the corpus, most notably in CH XIII. As a monist panentheistic system, everything in and out of Existence is contained within the One variably as within its essence or as present in its Incorporeal Imagination (cf. the Aiōn of CH XI).

Other online Hermetic commentators have already noted the distinction between Moral & Philosophical Evils, so I refer my readers to them for that. Needless to say, the Good, Beautiful & True are within God alone, and philosophical corruption lies with the realm of Generation that the SH describes as shadowy appearances, phantoms of falsehoods, masking the “true reality”. Our perception of change, corruption or distinction are merely that, perceptions. They are a product of warped human awareness and alterations of consciousness, not a reflection of things as they truly are.

I’m reminded here of the excellent discussion on Evil in theurgic Neoplatonism by Jeffrey Kupperman (2013), which I will paraphrase here20.

For someone like Iamblichus, who views not only the Good & Demiurge, but all the gods, daimons, angels and other members of the Greater Kinds as wholly and unchangingly Good, wanting Good and making Good, where can evil even fit into this schema?

Plotinus is clear in his admonishment of matter as being Evil. He does however admit that it’s impossible for evil to have self-existence in the formal sense of the world, because the Good is not only the source of everything it emanates but also that which is beyond it. For Plotinus, “evil” is simply an accident of language, not any real description. Evil’s nature is simply the opposite of existence, that is, non-being.21

In typical Iamblichean fashion, we should nuance things a bit and differentiate between something that is participating in evil and that which is the source of evil. For Plotinus, this source is the Absolute Evil, and opposite of the Good. Despite his defence of the Demiurge of the Timaeus as Good, Plotinus views matter as inherently evil, containing no true Form, being lifeless, lacking any part of the Good and is nothing but a hinderance to the proper functioning of the soul.

As Kupperman notes, while Plotinus is relying on the descent narratives of the Phaedo and Phaedrus for this view (which both present the soul’s embodiment negatively), he seemingly ignores the role of the Demiurge in the Timaeus as a fashioner of matter with the intention to make all things Good22

Late Platonist Metaphysics relies on models of emanation. Each level of reality is ontologically “less” than its former in the sense that it has less Being. For the later Platonists like Iamblichus, Proclus & Dionysius, matter (and embodiment) cannot be absolutely evil since -on account of Tim 36, it must participate in the Good through the agency of the Demiurge. Our physical world is still at the respective “bottom” of the Chain of Being though, and while the immaterials are present constantly to the materials, matter’s capacity to hold the influences of the Good is significantly reduced in comparison to everything preceding it.

I’ve written a previous post on the nature of matter already, so I won’t go into the specifics here, but the ethical overtones of this around the nature of Evil would undoubtedly been known to the authors of the Hermetica.

On account of the immaterials being present to the materials, matter and the world cannot be Plotinus’ Absolute Evil, but that doesn't necessarily make it all Good either, even if it does participate in the Good in some capacity. Matter, the Body and Existence isn’t evil qua evil but it is nevertheless a hinderance to the ascent of the soul, as the Good & unchanging beauty can only exist in God alone.

To elucidate this, I again turn back to Kupperman. Iamblichus uses Aristotle’s hyle to refer to material “stuff”, as it were. The cosmos and matter are creations, and therefore under the direction of the Demiurge(s), meaning that all of reality is penetrated by its logoi (reasoned-principles), which give form to things by communicating the Platonic Forms to them23. As I mentioned in the last article, these Logoi of the Demiurge “in-form” the Pre Existent matter and direct it to take shape, and therefore cannot be separate from it.

In this sense, matter acts as an accretion and substance (cf. substantiality & materiality in my prior post) to noetic suthenmata/symbola sewn throughout the cosmos. It is the effects of this matter-accreation that can be harmful and produce harm if self-identified with over the reasoned-principles themselves. Matter forms a kind of shell around the Pneumatic Ochema, especially for humans and sub-lunary daimons (usually conceptualised via planetary qualities). But again, strictly speaking, matter is a neutral consequence of embodiment. It is not evil, but the effects it has on certain noetic principles and beings can cause what we consider evil things.

This is not because matter “corrupts” generation, or that Vice is inherent in the embodied world, but because the accretion of hyle around something’s Ochema makes it harder for the emanatory power (and thus, the Good) of the prior ontological realities to penetrate it. This makes it naturally difficult for such things to participate in the Good, which -again, is the source of all Being. Unable to truly see through the accretions or false images causes such afflicted beings to deviate from their essence, and it is this going astray that produced what we call “evil” or “corruption”24.

This view is echoed by Proclus in his commentary On the Existence of Evil, where he described it as a parasite, having no real existence of its own. For him, on account of the mixed Good and mixed Evil, even things we perceive as wholly “evil” are in fact -at worst, mixtures of Good and Evil because the Good itself IS pure Being, and therefore the source of all things own Being.

Evil for Proclus is a misalignment of the proper reasoned ordering of something’s system. This is vital to understand as it implies that only certain kinds of beings are capable of evil or vice. Pure Intelligables or gods for example, are perfectly ordered above the Divine Intellect and so are incapable of it. Only pluralised parts can participate in evil, which occurs when the balance of soul is disrupted and not lead by Wisdom or Reason.

As a consequence, evil is not found inherently in any part of the soul, as that would give it self-existence. It is only to be found in the relationships between parts. That is, it only exists in the processes connecting things when such processes fail or misalign in some way. “Curing” evil then, is a process of restoring the proper relationships between ontological levels. Bodies are subordinate to Nature, Souls are subordinate to Intellect, and Intellect is subordinate to God.

A further nuance is outlined by Dionysius in his The Divine Names.25 In a discussion on the nature of evil daimons, he questions the very nature of evil itself. Iamblichus originally argued that some daimons, especially ones that intercede more frequently or closer to matter can become evil, even though they aren’t originally. In the same way, our soul, while not evil, can incline towards the physical/generative world where evil occurs, and begin to self-identify with it, thereby causing evil itself. Note that the generative world is not strictly evil, only the domain in which it has the potential to occur.

Evil can’t come from the Good, because it would then participate in the Good and not be truly evil. In the same way, evil can’t inherently exist in beings, because all Being derives from the ultimate Being itself, which is the Good. We know this by virtue of the fact that things exist at all, existence being derived from the principle of Being. The consequences of this are major. If something exists, it participates in Being, and if the Good and Being are synonymous (or in the very least coexistent and dependant), then by existing, something equally must come from the Good, and the Good cannot create evil.

It is impossible to be completely cut off from the Good, because to be so would also cut something off from Being, meaning it has Non-Existence, and therefore didn’t exist (at least in a capacity we can actually experience). For Dionysius evil is impermanent and only an appearance (parahypostasis) because only the Good is eternal26. Humans can certainly engage in evil things, but does that make them inherently evil? At any given time we may lack some element of the Good or Virtue, but evil as itself does not exist.

Evil is simply a lacking of the Good (Beautiful-True). To whatever extent something fails to participate in the Good, that process can be called evil. Thus, anything capable of not participating or receiving the Good has the potential for evil. Even things we perceive as completely evil though, still desire existence and being as a foundation, and therefore -albeit unknowingly, desire the Good.

One of the great many things I like about Dionysius is his differentiation of this lacking in relation to the evils of particulars, which helps transition us into the notion of moral or behavioural evils. For him, different categories of being can participate or tend toward producing evil in different ways. Notably27,

For spirits -such as daimons, evil is:

What is contrary for the good-like Mind

For humans, evil is being or acting:

Contrary to reason

For bodies, evil is:

Being contrary to nature

All of this in mind, it helps us understand what is meant by the enigmatic passage in CH II.14-15:

Except God alone, none of the other beings called gods nor any human nor any daimon can be good, in any degree. That Good is God alone, and none other. All others are incapable of containing the nature of the Good because they are body and soul and have no place that can contain the Good. For the magnitude of the Good is as great as the substance of all beings, corporeal and incorporeal, sensible and intelligible. This is the Good. This is God.

The idea here is that because God is the Good, the Good only exists AS God, and cannot be applied to anything independent of it, not that the rest of the universe is necessarily evil per se, except as mentioned above wherein certain particulars are limited in their ability to receive and contain the Good. Later on this is made explicit in CH II.16:

The Good is what is inalienable and inseparable from God, since it is God himself. All other immortal gods are given the name “good” by honour, but god is the Good by nature, not because of honour. God has but one nature, the Good. In God and the Good together there is but one kind, from which come all other kinds…therefore God is the Good and the Good is God.

When it comes to Hermetic Moral Evils, we have a fairly standardised moral list outlined by Poimandres in CH I 22-23 that gives us an insight into what was considered good and bad behaviour for Hermetists:

I myself, the Nous, am present to the blessed and good and pure and merciful—to the reverent—and my presence becomes a help; they quickly recognise everything, and they propitiate the father lovingly and give thanks, praising and singing hymns affectionately and in the order appropriate to him. Before giving up the body to its proper death, they loathe the senses for they see their effects. Or rather I, the Nous, will not permit the effects of the body to strike and work their results on them. As gatekeeper, I will refuse entry to the evil and shameful effects, cutting off the anxieties that come from them. But from these I remain distant—the thoughtless and evil and wicked and envious and greedy and violent and irreverent—giving way to the avenging demon who wounds the evil person, assailing him sensibly with the piercing fire and thus arming him the better for lawless deeds so that greater vengeance may befall him. Such a person does not cease longing after insatiable appetites, struggling in the darkness without satisfaction. This tortures him and makes the fire grow upon him all the more.

So, blessedness, goodness, purity, mercy, reverence and an attitude of detachment from senses on account of “seeing their effects” are all listed here as behaviours befitting a devotee. Interestingly, we see here one of the consequences of engaging in vice/poor behaviour:

I will refuse entry to the evil and shameful effects, cutting off the anxieties that come from them

Poor behaviour and vice is its own punishment, as it produces symptoms of anxiety, which cuts us from seeing and experiencing the beauty that is God present in the world. In the same way, thoughtlessness, evil (to be conceptualised as an absence of virtue or the Good in our daily actions), envy, greed, violence, irreverence, lawlessness and an insatiable appetite are all characterised as behaviours which keep the Divine distant from us.

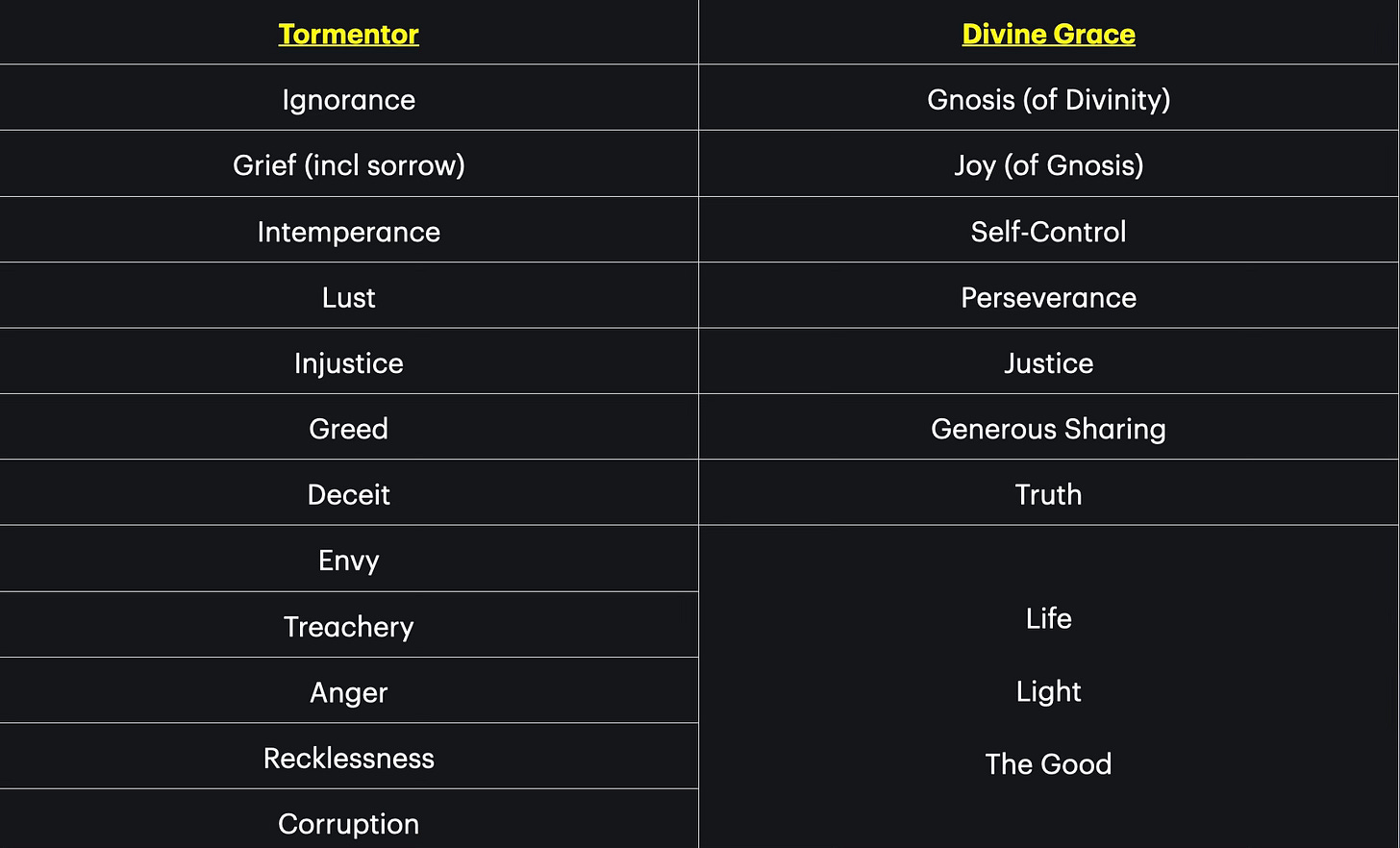

We then also have the interesting list of “Tormentors” and corresponding Divine Powers outlined in CH XIII:

On the surface, these look like a good moral framework for a practicing Hermetist, but i’ve mentioned elsewhere in classes the danger of taking this list as any kind of canon. They also aren’t technically Moral Virtues, although they could theoretically serve as a framework to aspire to in terms of one’s actions. They are Divine Powers that constitute the Reborn Body free from the Passions.

While the Doctrine of Passions was central to Hermetica, it is not in itself a Hermetic concept, being attributed in origin more to the Stoics and was largely ubiquitous in philosophical circles in Late Antiquity.

Zosimos in his Final Quittance28 seemingly alludes to this treatise, but interestingly lists slightly different harmful emotions as Passions or vices that stand in the way of calling the Divine Powers into you:

Do not allow yourself to be seduced, O woman, as I explained to you in the book concerning Action. Don't wander off looking for God; but remain seated in your room, and God will come to you, he who is everywhere; he is not confined to the lowest place, like the demons. Rest your body, calm your passions, resist desire, pleasure, anger, sorrow and the twelve fatalities of death. By directing yourself in this way, you will call the divine being to you, and the divine being will come to you, he who is everywhere and nowhere.

Some of these are familiar to those we see in CH XIII; mainly Sorrow and Anger. Desire could be argued to be equivalent to Lust, but not conclusively. He lists the first four Passions as separate to the “Twelve Fatalities of Death”. Are we to assume he includes them in that list, implying there are 8 further ones? Or are the prior 4 considered separate to another (different) list of 12?

In such a case, while the essential Doctrine of Passions may be shared among Hermetic practitioners, which Passions or Harmful Emotions were considered obstacles or vices may very well differ between communities or lineages.

Regardless of specifics though, what was the overarching framework that lay behind why one should practice Virtue in Hermetica?

On the one hand, we can turn back to Ascl. 11 for a fairly succinct justification:

What prize do you believe such a being should be presented?…Is it not the prize our parents had, the one we wish. -in most faithful prayer, may be presented to us as well if it is agreeable to divine fidelity; the prize, that is, of discharge and release from worldly custody, of loosing the bonds of mortality so that God may restore us, pure and holy, to the nature of our higher part, to the Divine?

This is a fine justification, but I’m still not satisfied with it as a framework or model of ethics. To understand more of that, I turn to the Korē Kosmou, preserved by Johannes Stobaeus .

Ethical Frameworks & Schemas in the Korē Kosmou

Stobaeus is incredibly important in my opinion, as he shows no signs of Christian identity, and was explicitly only interested in non-Christian writers29. As a necessary aside for a moment, I must say this is one of the major areas where my opinion diverges from Wouter Hanegraaff’s in a big way.

In his recent Hermetic Spirituality book (which I adore, and consider absolutely necessary reading if one is interested in Hermetica) he attempted a reconstruction of a “Hermetic Spirituality”, in which he groups various treatises -accounting for Christian interpolation, by their “weirdness” and how far they correspond to his notion of

What the Hermetic path was really about

Which most commonly is presented as a path of spiritual exercises, philosophical contemplation and ritual practices designed to heal the soul and free the body from the Harmful Passions to enable us to “give birth in beauty” and achieve Gnosis of the Pēgē30.

He clearly advocates that the “centre” of Hermetism in Late Antiquity is thought to be this Hermetic Spirituality, which was concerned with:

A supra-rational gnosis that can be accessed only by an enigmatic faculty called Nous31

Now, I don’t necessarily disagree with this. I actually think he’s spot on when it comes to things like the Passions, Spiritual Exercises & the role of the Imagination and Altered States of Consciousness. Where I take issue is his exclusion of certain Hermetic texts on the grounds that they have:

Little or no relevance to Hermetic Spirituality32

The main collection he argues were “central” in his view are CH I, XIII & NHC VI. But he excludes CH III (itself perhaps better characterised as proto-hermetic) and XVIII on the grounds that “only the title is Hermetic” for the former, and “[CH XVIII] is a piece of rhetorical praise of God and Kings, without any clear connection to the Hermetica”33. Given Reitzenstein’s findings34 that the “kings” in question in CH XVIII are the Augusti, Diocletian and Maximian and their Caesars, Galerius and Constantius, he is perhaps more justified in the latter. Although I’d question the notion that discussions and praise of Royal Souls and Kings have “no clear connection to Hermetica” given the Doctrine of Royal Souls’ centrality in the Korē Kosmou.

But this is the much bigger issue for me. Hanegraaff equally excludes SH 23-27 as part of the [Spiritual] Hermetic Corpus on the grounds that:

They are sharply different from the rest of our treatises in terms of their alleged authors, contents, worldview and literary style. Hermes does not appear either as a teacher or as a pupil, instead, we read conversations between Isis and Horus in which the All Knowing Hermes is presented as a Divine Ancestor. The mythological narrative describes God as an anthropomorphic, and authoritarian Craftsman who punishes souls he has created for transgressing his commands. The great beauty of the higher world does not inspire love and admiration but fear; and when the souls are disobedient, they are punished for their sins by imprisonment in the “dishonourable and lowly tents” or “shells” of material bodies. Throughout, the emphasis is on God’s despotic power and his creatures’ fear of him. I see all of this as incompatible with what we find in the rest of our corpus. I assume that these Isis-Horus treatises represent a separate tradition.

I completely agree with Hanegraaff’s assessment that the Korē Kosmou constitutes a different tradition and intellectual climate, and it almost feels to me that it potentially came from a different -perhaps rival, Hermetic community to the one that composed the Corpus Hermeticum. Notably, one that represents as offshoot of the classical Hermetic lineage (from Hermes to Asclepius/Tat) and sought to emphasise the teachings that were passed to Isis via Agathodaimon and elucidated by Hermes35.

But I struggle with the notion that the text (and in turn, the community/climate that composed it) is any less Hermetic.

The Korē Kosmou clearly contains native Egyptian elements, I’d even argue more explicitly than our Corpus Hermeticum in its preservation of two Egyptian creation accounts. It is known to have been composed from several different sources to form an episodic format, given that it contains internal tensions.

Hermes does indeed appear as a central character in the narrative, not only occupying a central role as the creator of human bodies, but God also identifies him as the “soul of my soul, Nous of Nous” who gathers all the planets together in council36. Hermes is equally the originator of the entire dialogue that Isis is giving to her son Horus. We see the characteristic Hermetic Lore myth of Hermes inscribing his wisdom on secret stele in Egypt that are later found and used for instruction in the present text37:

This…Horus..could not be accomplished by mortal seed -which did not yet exist, but by a soul corresponding to the heavenly mysteries. This was the soul of All Knowing Hermes. He saw everything. When he saw, he understood, and when he understood, he had strength to disclose and to divulge it. What he understood, he inscribed; and when he inscribed it, he hid it, keeping most of it in unbroken silence rather than declaring it so that every future generation born into the world might seek it. This done, he ascended to the stars to accompany the gods who were his kin…He was to deposit the sacred symbols of the cosmic elements near the hidden objects of Osiris, and then, after praying the following words, return to heaven

Later on this is made even more explicit in SH 23. 67-8:

After they (Isis & Osiris) learned from Hermes that the ambient was full of divinities, they inscribed it on hidden steles. They alone, after learning from Hermes the secrets of divine legislation, became initiators and legislators of the arts, sciences and all occupations. They learned from Hermes how lower things were arranged by the Creator to correspond with things above, and they set up on earth, the sacred procedures vertically aligned. with the Mysteries of heaven

I also disagree with the notion of a damnation style punishment for the souls, and that the presentation of God in the Korē Kosmou is as a “despot” or authoritarian figure. God is depicted more as a loving father who isn’t afraid to teach his children hard lessons if it means they will come to appreciate Beauty & understand their role in creation. I think it’s important to point out that souls initially stray from their stations out of curiosity and “daring” -itself reminiscent of Plotinus, not really any kind of sin or direct disobedience.

Souls are embodied as a “punishment” for straying from their Astrological Stations, yes, but it’s really more of a chastisement designed to train and improve our soul, not any kind of eternal damnation. The point is not to degrade into nothing or for a sadistic God to separate us from himself, but to give us a chance to improve our essential quality through humility and experience. Improvement in this context means learning to fulfil our original function as overseers of the stars and become whole.

A general reading of SH 23.25-30 makes it clear the point of embodiment is to make the cosmos an object of admiration for souls, not just something we are part of the machinery of.

It’s in this essential section that, I feel, we find a much deeper elucidation of a Theory of Hermetic Ethics.

On the Purity & Quality of Souls: A Summary of the Korē Kosmou

Now, it’s worth recounting a brief summary and context of what the Korē Kosmou contains for my readers who haven’t read it yet. A large amount of the theme in this collection focuses on Transmigration.

The account of the creation of souls in SH 23 is absolutely fascinating. God makes Soul (likely identified here with the World Soul) by mixing his own breath with the purest type of fire and other “unknown elements”. He does so in a mixing bowl, pronouncing “sacred and secret formulas” over a bubbling mixture, stirring everything together vigorously like an alchemist until it bubbles/foams, which Father Festugière noted bears a resemblance to the process of refining philosophical Mercury38.

It’s these secret formulas (perhaps to be interpreted as nomine magicae) that unite the soul’s composite elements together and imbues them with light and imperishability.

This soul-material (not yet distinguished into individual souls) is called Psychosis39. This Soul-Substance is split off into 6040 different grades of purity, implying souls can be of different qualities, even before incarnation, although Hermes is quick to point out that41:

Still, the Craftsman legislated that all souls be eternal, since they were from the same substance which he alone knew how to perfect

So, despite the grading system, all souls are of the same material, differing only in quality or grade, which is malleable and within our own remit to perfect. Souls are then given stations to control the stars. This is important, as in their origin, astral bodies are inferior to the human soul since they also contain earthly and watery elements, whereas our soul is pure divine fire and breath (pneuma).

Souls are charged with creating animals, for which they follow the Forms of the Zodiac, created by God using a diluted form of the Psychosis/World Soul. Souls are eventually “punished” for being disorderly and idle in their stations. There is also an added suggestion that our souls are naturally curious and desire to pry into God’s creation before they are at a sufficient quality or receptivity to actually understand it.

The chastisement for this act is embodiment, conceptualised not necessarily as a Fall, but as being surrounded by denser, coarser and sluggish elements. Interestingly, Hermes is the one who makes the human body from a diluted and degraded form of the Psychosis. I want to restate that, because it’s vitally important.

Our body is made out of the same substance our soul is.

The only difference is that our soul is a higher grade of purity & isn’t watered down. I actually mean this literally. When making our bodies, Hermes attempts to use the same Psychosis mixture, but finds it has dried up, so he adds copious amounts of water to make it malleable again42:

When I received [the soul-substance], I found it completely dried up. Then I used much more water than was necessary for the mixture to refresh the composition of the material. As a result, what I formed was entirely dissolvable, weak and powerless.

Transmigration in this dialogue is seen as a method of training our souls, and the generated Cosmos is essentially one giant boot camp for learning virtue and preparing our soul. In theory, if we learn the lessons in a single lifetime, we won’t need embodiment again, but most people will require multiple trials. Again, there is no hell here, embodiment is simply an opportunity to improve the quality and grade of our soul.

Souls who need more intense training (i.e tyrants, murderers etc) pass into animals and have rougher, shorter and more brutal lives. Interestingly, the pejorative tone present in Ascl. 12 that speaks of a “vile migration” isn’t present here. Even if it were, the “vileness” can still be implied in comparison to a human incarnation, even if it isn’t permanent.

Souls who have learnt their lessons and practiced virtue go into purer bodies, ones more endowed with Reason, which also translates to higher occupations during earthly life; things like Kings, Philosophers and excellent Musicians. In fact, we get a rare look at some professions that are esteemed in a Hermetic author’s eyes in SH 23.4243:

You souls who are more just and who are able to receive transformation into divinity will enter humans as just kings, genuine philosophers, founders of cities, lawgivers, true seers, genuine root-cutters, most excellent prophets of the gods, experienced musicians, intelligent astronomers, wise augurs, accurate sacrificers, and whatever noble vocations there are of which you are worthy

The goal is eventually for our soul to return to a body with such a degree of purity and subtlety that it can retake its place among the stars and fulfil its original position, commanding and directing the planets & machinery of Fate -in theory, with all of the knowledge and experience it has amassed over lifetimes to mediate such Fate justly44:

The variations in your rebirth will consist in the variation of your bodies; and the dissolution of the body will be a benefit and a return to your former blessedness. If you plan to do anything unworthy of me, your Nous will be blinded. As a result, you will think wrongheadedly, endure your punishment as if it were a boon, and consider promotion a dishonour and an outrage

When souls are initially embodied, they go berserk and shriek because they’re not used to it45. To tame the souls, Fate (which is the combination of Decanic & Astral Energies) is introduced to control the human body. Notably though, Fate can only control the Body (and the Passions) since our original soul is of a higher grade of purity and therefore above its influence.

This cosmology and anthropology matches Iamblichus’ discussion of “the Egyptian account of souls” in DM 8.6:

Into this latter soul slinks the God-Seeing soul. This being the case, the soul which descends to us from the Celestial Realms accommodates itself to the circuits of those realms, but that which is present to us in an intelligible mode from the intelligible realm transcends the cycle of generation, and it is in virtue of it that deliverance from Fate comes as well as the ascent to the intelligible gods

Isis & Osiris then come into the world in ancient times (and are conceptualised as souls not in need of embodiment, but are sent to educate and civilise, directly from God) and its from their religious and spiritual teaching -based on that of Hermes, that all religions and cults are formed and the “way that leads above” is rediscovered.

Soul in this Hermetic tractate is composed of divine breath. It is a distinct entity and a unique energy in the Cosmos46. We are Good and our “good” is held within us because we are literally the breath of God. We are here, in bodies, training to take back our original function of controlling the Cosmos and being higher than the stars, consequently attaining a body that is not subject to the passions, death, disease, fear etc.

The implications are that all living beings have souls (incl animals)47, and that souls can be transferred from body to body. All creatures then deserve respect on account of their souls, and this grounds our ethics towards animals48. Souls are also neither male nor female (although described with feminine pronouns before embodiment), gendered definition being a generated quality, and the kind of life energy that humans have is the same in all animals.

The practice of virtue is essentially rewarded with grades of freedom from heavy, mortal elements, conceptualised as changes in the grades of our soul mixture. Virtuous humans eventually return to their Stellar Bodies, by exiting the gross elements and constructing a body out of their Purer Materia49, likely implied to be Aether or the highest Air.

Horus then gets interested in the idea of Royal Souls, that is to say, the souls of kings & rulers. This is where things get interesting.

The Doctrine of Royal Souls

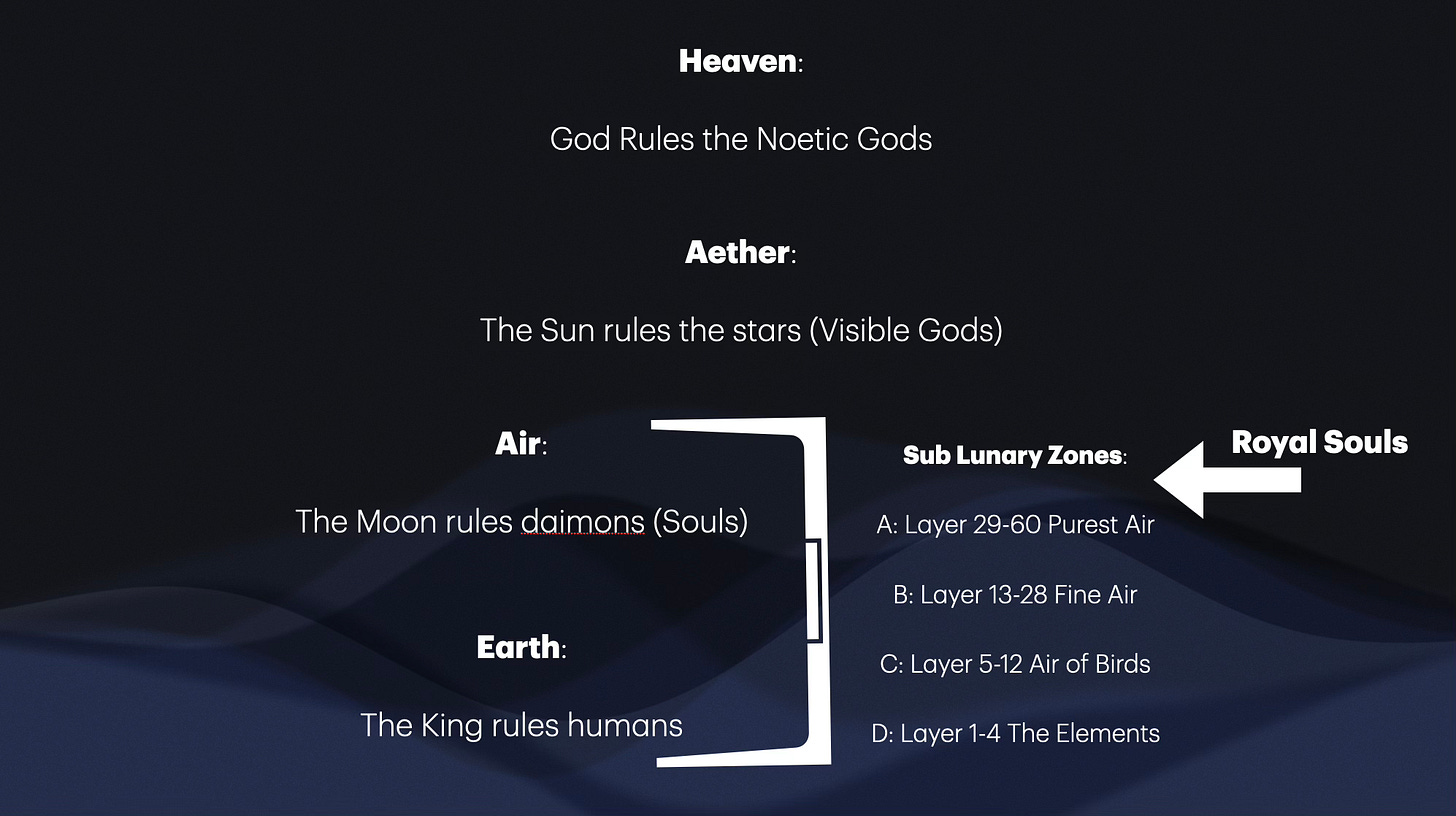

Here, we’re looking clearly at a justification for an Egyptian Kingship system. Isis tells us that each realm of reality has a ruler:

Heaven (Nous) is ruled by God and populated with Noetic Beings

Aether (the purest form of air) is ruled by the Sun & populated by the Visible (Encosmic) Gods

Air is ruled by the Moon & is populated by daimons and the vast majority of souls

Earth is ruled by a King & is populated by embodied humans

The king here is assumed to have a higher, purer soul, more closely associated with God, and perhaps Heroic Daimons, originally coming from the highest level of the Air (just below the Aether). The King is therefore the lowest of gods and highest of humans, and bridges, ontologically, and overlaps these two domains. This doctrine of the lowest of one ontological category overlapping with/being identical to the highest of the one below it is equally attested by Iamblichus in many of his known works.

Noble people, or those who excel in their profession or art also appear to have higher grades of souls, derived from ontologically higher realms in this Chain, because there are many grades of soul that live in corresponding grades of Air outlined in SH 25 11. The Air and Sublunary divisions also appear to have been considered the domain of human souls after death while in a kind of intermediary state, awaiting transmigration, reminiscent of the restless dead often called on in magical papyri.

Souls after death go to one of these 60 levels of the Air depending on the quality of their Psychosis -that is, soul mixture, not mental state, and virtue. Quite simply, the higher you go, the purer the Air becomes, which equally has an effect on the quality and perception of the soul, almost as a correspondence. In theory, the higher through the grades you move, the more of your noetic perception you have access to. Therefore, this can be seen as the classic Hermetic trope that alterations of state or quality coincide with alterations of consciousness and perception.

This idea that air quality affects intelligence or perception is equally found among the Stoics, for instance, in Cicero’s On the Nature of the Gods 2.3–164:

Indeed, one may observe that people who live in lands blessed with pure and thin air have keener intellects and greater powers of understanding than people who live in dense and oppressive climatic conditions.

The modern environmental/climate crisis overtones of this aren’t lost on me…it brings a whole new consequence to pollution in cities.

The purest, most translucent air at the height of this system is Aether, while the lower, denser air is closer to the Earth. Most souls abide in the median Air, within the Sublunary Zones after death, in the same location as aerial daimons. Interestingly, both are ruled over by the Moon in SH 24. 1, and from some quick correspondence research outside of the SH, looking at the PGM for example, it’s really not a leap to suppose Hekate mediates and rules this group.

Our world system is ultimately a meritocracy in this cosmology. Our soul’s quality, although initially predetermined before incarnation is also determined and affected by our practice and profession in life. In a nutshell, the more that we do what we’re supposed to do while embodied, the purer the quality of our soul becomes, increasing its receptivity to and perception of the divine.

To help mediate the right souls being in the right bodies and under the right rulerships, we are told there is a kind of middle management system of celestial rulers, notably Memory & Experience in SH 26.4, who ensure that souls are matched up with the right kind of bodies to fit their quality, receptivity to the divine, and presumably, who’s life trajectory will contain the lessons required for further improvement.

As an aside, this does remind me of the discussion that Hermes' has with God in SH 23.28 just before the creation of human bodies and the whole embodiment process begins. While discussing the imparting of qualities to the body (and, theoretically, the Pneumatic Vehicle alongside it), we have a really interesting list of “Gifts from the Planets”. Importantly, these gifts are largely positive in stark contrast to the sheaths that are shed upon ascent in CH I.

Hermes -here acting as Mercury, we are told50:

Will make human nature…and entrust them with Wisdom, Moderation, Persuasion and Truth. I will not cease to join with Invention…I will forever assist the mortal life of future humans born under my zodiac signs [Gemini & Virgo]. The signs that the father and Craftsman entrusted to me are wise and intelligent. I will benefit the race all the more when the movement of the stars that overlie them are in harmony with the nature energy of each individual

Christian Bull notes a pivotal point in reference to this section51:

The implication of all this is that just as the souls of human kings, the souls of sages, who deal with “counsel,” also emanate from the royal stratum of souls, just below the gods. Sages can thus presumably “manifest” Hermes, in the same manner that the Egyptian kings “manifest” Horus. Indeed, the different kingships enumerated here correspond to some of the favoured rebirths for humans in their migration towards the divine. Hermes and these other god-kings thus represent the hope of the souls under their dominion to ascend up to heaven, to the company of the gods, where they dwelt before their disobedience made God enclose them inside material bodies.

In the anthropogony of the Korē Kosmou, Hermes declared his willingness to aid those who belong to him [quoted above]…the signs of Hermes are Virgo and Gemini, and Firmicus Maternus affirms that Mercury in favourable positions creates “philosophers, teachers of the art of letters, or geometers”; astrologers who “contemplate the presence of the gods, or men skilled in sacred writings”; orators and lawyers; and even “great men crowned with wreaths for being famous in sacred matters.” Hermes is thus not only the patron god of letters and sacred matters, but he is also in some sense the king of them, and the archetype that all those who pursue these arts should emulate

To me, this reads almost as an archetypal, aspirational framework. Hermes as the Divine Model of the Philosopher-Sage presents the initiate born under his rulership (and thereby endowed with his qualities) with the Form to aspire to. In theory, each Encosmic (Planetary) Deity does this, and the Planetary Intelligence/Deity itself perhaps serves as a model patron, who’s behaviour one should seek to emulate as far as they are able while in the body.

In other words, the ruler(s) of our Natal, alongside our Personal Daimons provide a key insight into our purpose in life and the means by which we acquire our Perfect Nature.

Coupled with the idea in the Asclepius that the point of our embodiment is to give birth in Beauty and align our little portion of the world with the Ideal Form and God’s Will, that is, to contribute to the creation of Beautiful (Good & True) things within our remit of influence, perhaps our Natal and Planetary Rulerships gives us an insight into what that is, and the deity(s) who rule over us provide us with a framework to aspire to -in terms of behaviours, ethics, mannerisms etc, in order to fulfil it and achieve higher transmigrations.

Hermes himself is presented sometimes as a human, sometimes as divine, and sometimes in between. But here, his role becomes clear. He was a human who attained apotheosis based on the principles of Mercury -those of the Philosopher-Sage, and now occupies that Formal Reality himself as the planet Mercury, serving as a semiotic figure and archetype for the model ethical behaviour of the philosopher -one born under Mercurial influence. And presumably, the other planetary gods are the same.

Such an idea is perhaps supported by SH 26.9:

Isis: For there are many kingships; some are kingships over souls, others over bodies, others of an art, others of learning, and yet others of this and that.

Horus: What do you mean?

Isis: This, my son Horus. The king of those souls who have already passed away is Osiris, your father. The king of bodies is the chief of each of the races. The king of counsel is the father of all and guide, Hermes Trismegistus. The king of medicine is Asclepius, son of Hephaestus. The king of strength and might is once again Osiris, and after him, my son, are you yourself. The king of philosophy is Harnebeschênis, and of poetry it is once again Asclepius Imouthes. In general, my son, if you examine the matter you will discover many rulers of many things, and many kings over many things.

We must also remember that transmigration also includes animal bodies. We’re not sure if all animals were human souls, or only specific ones, but clearly a lot of them are.

So what are we to make of all this?

All human occupations fit into a natural hierarchy depending on the quality of soul incarnating. Certain professions or occupations are clearly more important to the hermetic author, which are filled with purer souls. Each occupation has a ruler, usually a planet or deity who is always available to aid those who come under their remit in terms of soul and profession.

The substance of our soul doesn’t change, but its quality is modified by various elemental vapours that surround it like a sheathe, as well as our behaviour and the practice of virtue.

Egypto-Centrism: On the Purest Air & the Temple of the World

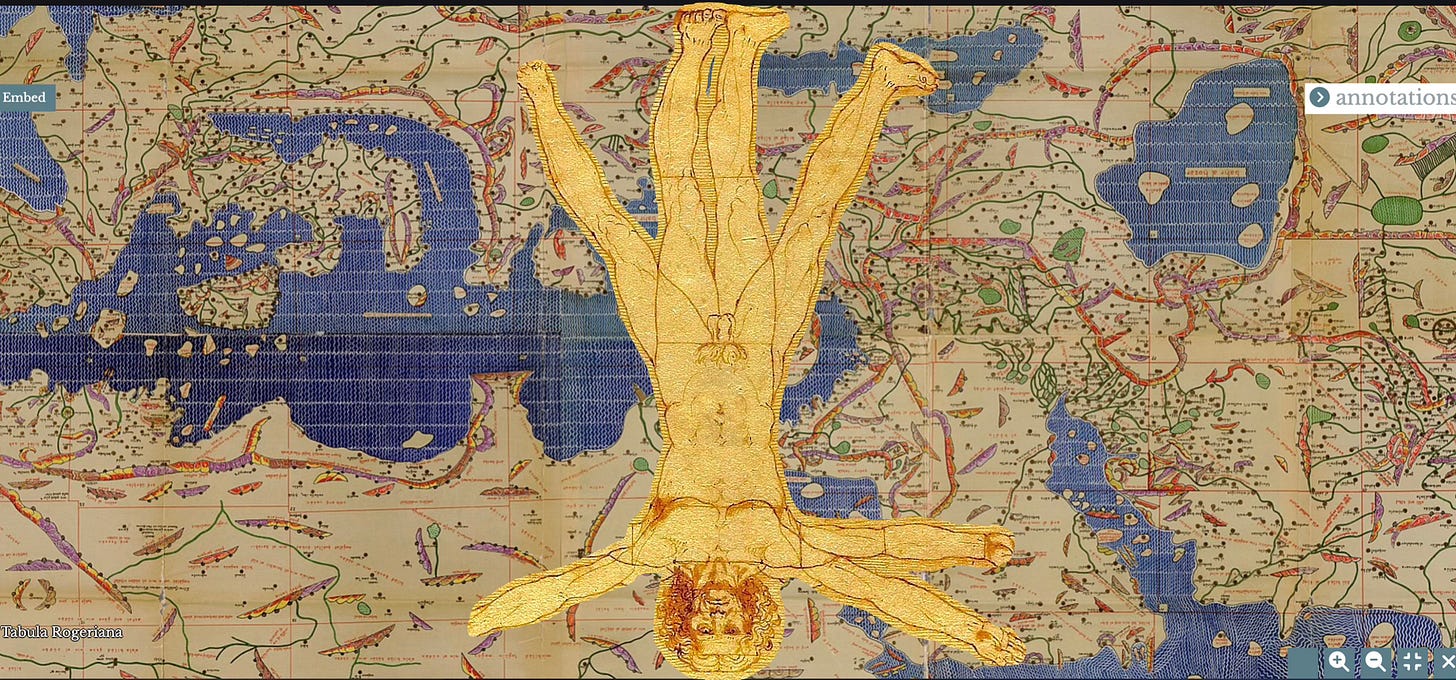

Something that I think is missed often is that this text is very ethnocentric. Egypt is coded as the centre of the world, which to a Graeco Egyptian author, makes sense because on their maps Egypt is in the centre. Sacredness is coded in its centrality, almost as a kind of World Axis or central pillar. Egypt has the most temperate climate, which produces the most receptive intelligence.

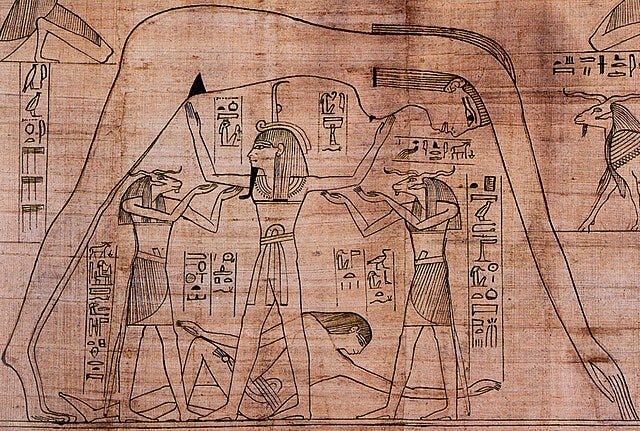

The earth is conceptualised in SH 24.11 as an upside down woman, lying on her back, whose heart is resting over the location of Egypt:

The earth in the centre of the universe lies on its back like a person viewing the sky. She is divided into as many limbs as the human body possesses. She looks up at the sky as to her own father so that by his transformations she can coordinate the transformation of her own properties. Her head lies toward the southern portion of the universe, her right shoulder to the east, her left shoulder to the west, her feet are under the Bear constellations in the north, her right foot under its tail, her left foot under the Bear’s head. Her thighs, in turn, are in the regions that come before the bear, and the centre of her body under the central regions of the sky.

This is consistent with native Egyptian theological understanding of Geb, the earth god as being supine, gazing up at the Sky (Nut).

Egypt as a country is placed on the heart of the World-Human. According to Egyptian tradition the heart was the centre of intelligence and soul, not the brain, which is the reason Egypt is the temple of the whole world. The country literally occupies the space of the heart in the bodily proportion of the World-Human.

Conclusions

So what are we to make of all of this in terms of an ethical framework in Hermetic literature?

The schema on display in the Korē Kosmou is one of ethically and virtue dependent transmigration. It’s essentially a kind of Hermetic Karma.

Our behaviour, actions and -to some extent, profession (in the sense of how we contribute to the world), during life directly affects the grade and quality of the substance of our soul. By engaging with virtues and avoiding vices, we gradually improve the quality of our soul -alongside intellectual cultivation and ritual practice, which secures -or even perhaps creates, finer and purer Pneumatic & Luminous Ochema that we inhabit upon a new incarnation, until we eventually develop one that resides back in its original, pre-embodied state, which is above the Decans and Stars so that we can fulfil our purpose of admiring the universe and maintaining it as a direct child of God and, if the Corpus Hermeticum is anything by, a sibling of the Demiurgic Intellect.

Important to remember is that the actual substance of our soul doesn’t change here, but its quality is modified through our actions.

Every soul is created equal and Hermes is clear in his assertion that every soul is a Royal Soul. So this also isn’t as classist/elitist as it may first appear. Everyone’s destiny is as a Royal Soul by virtue of the fact that we are all created from the World Soul/Psychosis. The differentiation of souls by quality serves a purpose, whether it be to rule and direct, create or whatever else. We all progress through different bodies depending on what specific lessons we have to learn to attain a higher position in that cosmic hierarchy at any given moment.

It is the practice of Virtues like eusebeia, goodness, reason, self control, and mercy that helps secure a new kind of Reborn body, free from Vices like ignorance, grief, selfishness, greed, envy and other harmful emotions. However, this generative Cosmos is precisely the training room in which we learn to overcome the Passions and secure that virtue, and we will incarnate into different bodies until we learn. Importantly, this is not to be considered a kind of Samsara or Prison, we are not stuck here, by any force other than our own unwillingness to learn or appreciate the Beauty of the world & God.

As guides on which to model our behaviour and actions, the gods exist in a state of unchanging goodness, virtue and generosity, and are always available to assist those born under their remit to become, well….themselves.

Future Questions & Directions

I will say, on a practical level, the 60 Zones of the World Soul are pretty underutilised in modern occultism as a cosmological framework, so I’d really like to see more people engaging with the Korē Kosmou as a practical text. The discussion of souls sharing the same space as aerial daimons and being ruled by the Moon has obvious links to lunar and necromantic rites in the PGM associated with Hekate, and She equally holds the position of Power and membrane of the World Soul in the Chaldean Oracles. Further work with her would yield interesting results, i’m sure.

The schema of Planetary “Gifts” outlined in SH 23.29 is unique in Hermetic cosmology for showing a positive side to planetary physiology and the qualities imparted to our Subtle Vehicle. Combined with the hexameter poem On Fate, in SH 29 we have a much fuller map here of planetary qualities to work with other than those negative ones listed in CH I. Further experimentation with corresponding suthenmata in this framework would be necessary, but I think, fruitful.

Addey, C. 2014: Oracles, Dreams and Astrology in Iamblichus’ De mysteriis. In Curry, P and Voss, A. eds., Seeing with Different Eyes: Essays in Astrology and Divination, 35-57. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Most usually in the form of an philosophical paideia or curriculum, as Iamblichus espoused in the order of reading Plato’s dialogues.

Valantasis, R. 1991: Spiritual guides of the third century : a semiotic study of the guide-disciple relationship in Christianity, Neoplatonism, Hermetism, and Gnosticism. Fortress Press: Minneapolis

Hadot, I. 1986: The Spiritual Guide. In Armstrong, H, A. ed. Classical Mediteranean Spirituality: Egyptian, Greek & Roman. 436. Crossroad: New York

See his essential study Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1995

I am indebted to John Opsopaus for this explanation

While too long to go into in this article, Greg Shaw’s discussion of Platonic Yoga also provides a key distinction from magic. This tradition of spiritual exercises -that has been lost to us, would have served to control the ego and act against the impulsiveness of desire-based magic.

DM II. 11. 10-15

See for example, Fr. 90

Se CH 16 for a discussion on the Astral Daimons possessing the internal organs of the body

See Chpt. 7 of his recent Hermetic Spirituality.

Van den Kerchove, A. 2012: La Voie d'Hermès: Pratiques Rituelles Et Traités Hermétiques: 77 (Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies). 191-192. Brill

For example, Ascl 11, 13, 34, CH XI 3, 6-7

On this, see Ward, J.K. 2021: ‘Plato’s Contribution to Theoria’, in Searching for the Divine in Plato and Aristotle: Philosophical Theoria and Traditional Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 50–85.

I’m making a mental note here to experiment with cultivating a devotional practice to Eusebeia as a kind of personal daimon

HSatHI, 197

The style and content is fairly typical of Late Demotic Wisdom Literature

Emphasis my own here to highlight that Disdain doesn't improve the quality of Goodness in itself, but notably our ability to perceive the Good

Kuperman, J. 2013: Living Theurgy: A Course in Iamblichus’ Philosophy, Theology & Theurgy. Chapter 5. Avalonia Books.

Enn 1.8. 2-3, 57-8

Tim 36d-37a, 41a-46c

This non-dualist view of the Forms as being constantly present to their images rather than in some separate, transcendent reality is noted by Shaw as the core argument of the Parmenides.

This notion of missing the mark of something’s true essence helped lay the groundwork for the Christian notion of Sin, albeit in a changed and more personalised form

Notably in the second half of chapter 4

DN IV. 23. 725A-B

All of these come from DN IV. 32.733A

FQ 8

Although notably, Christian Wildburg claims that the interpolations and edits in Hermetic literature preceded the 5th century and Stobaeus

His own definition of Hermetic Spirituality given in the prologue of his book is that it is “a joyful path that celebrated life and light. Its purpose was to heal the soul from negativity, free it from such powerful influences as fear and aggression, and open its eyes to the beauty of existence. It was not concerned with domination but with knowledge and understanding -or, more precisely, with knowledge as understanding.” HS. p. 10

HS 137

HS 139

He does note his reliance of Scott, Mahé and many other Hermetica scholars for this interpretation however.

See Copenhaver, 208-9

See Litwa (2018)’s introduction for a discussion on the topic of a Hermetic community focused on Isis

SH 23. 26

SH 23. 5-6

Mystique, 233-40

Notably, nothing to do with the modern term meaning a kind of mental breakdown. In the Greek context, Psychosis meant “giving life or animation” to something

A number which will become important later in the divisions of the World Soul

SH 23. 16

SH 23. 30

As Litwa notes, the majority of these professions are all chiefly those of Egyptian priests, but the notion of reincarnation into high status individuals is also present in Empedocles and Plato

SH 23. 41

SH 23. 31

See SH 23.15

Based on other SH, it doesn’t seem other animals have Reasoned-Nous however.

A lot is often made of the “Pythagorean” “Bloodless Meal” mentioned in NHC VI, with claims of Hermetists being strict vegetarians. This isn’t out of the question given the passage here, but to attribute complete vegetarianism to Pythagoras is a mistake. Isocrates’ clearest fragments paint a picture of Pythagoras as a ritual and religious specialist more than anything else, who “more conspicuously than others paid attention to sacrifices and rituals in temples” (Busiris 28). There is no evidence for dietary restrictions in Pre-Aristotelian sources or fragments.

The sources are inconsistent though. We might assume vegetarianism based on Empedocles (Frag 137) & the belief in transmigration, as here. Porphyry records that Eudoxus remarked that Pythagoras “abstained from animal food but would also not come near butchers and hunters”. Equally, among Aristotle’s school, Dicaearchus records that Pythagoras believed all animate beings were of the same family, but Aristotle himself contradicts this in his Aulus Gellius, saying “the Pythagoreans refrain from eating the womb and the heart, the sea anemone and some other such things but use all other animal food” (4.11.11-12).

If we follow Aristotle, it seems Pythagoras forbade eating certain parts or species of animals, but not all, which we have numerous parallels to in traditional Greek religious purification and Hermetic Decan books. Aristoxenus points out that, while he refused to eat oxen or rams, he did eat goat & “suckling pigs” for food. Iamblichus equally reports an acusma (citing Aristotle) that in response to the question “what is most just?” Pythagoras answered “to sacrifice”, in the manner of traditional Greek religion, meaning animal sacrifice, which would be inconsistent with not harming them.

Iamblichus does however attempt to get around this by explaining that Pythagoras thought it was legitimate to kill and eat sacrificial animals, on the grounds that the souls of men didn’t enter into them. The other major famous prohibition was against eating beans, first attested by Aristotle, who believed they shared a connection with Hades, and therefore also transmigration. The beans in question would likely have been vicia faba in Pythagoras’ time, which have been known to be difficult to digest and cause blood abnormalities in certain conditions. Again though, Aristoxenus completely contradicts the idea that he forbade beans.

SH 23. 39-40

SH 23. 29

Bull, C. 2018: The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus. 119.